I will no longer be posting to psycheandnature.wordpress.com. Please visit my new site at: psycheandnature.com. If you are a subscriber, you will continue to receive updates. Thank you for following! – Betsy

Note: This short piece has been submitted to Circles on the Mountain for publication.

For better or worse, wilderness rites of passage programs have gained a great deal of popularity over recent years. For better, because many of us have worked hard to see meaningful rites regain their importance within modern culture. We know that there is no lack of evidence that points to the social and environmental diseases brought about by a largely uninitiated adult population. And it certainly doesn’t take much effort to see that mainstream Western society is more concerned with possessions and personas than with the 7th generation, or even the present generation for that matter. For these reasons and more, the increased interest in rites of passage is a good sign that people are responding to an innate, but largely forgotten, structure for maturity and survival.

But the bad news is that we are also witnessing the commercialization of that which we hold with such sacred regard. A quick Internet search on vision questing(1) reveals just how liable these ceremonies are to being watered down into something they were never intended to be. It is not uncommon, for instance, to come across a weekend gathering advertised as a rite of passage, or a ten-day program wilderness program touted as an experience that can fill the void in one’s soul. Certainly, there is nothing wrong with weekend workshops and self-fulfillment, but neither of these expresses the enormity of an initiatory passage, which can take months, if not years, to undergo. We all know this, yet it is counter intuitive to market one’s rites of passage program as that which may foster a descent into the underworld, or produce more gut-wrenching questions than answers.

Initiation of Gilgamesh through death of Enkidu

When I really think about it, I find it astonishing that anyone in their right mind would choose to embark upon such an ordeal. Rites of passage ceremonies throughout time and place are notoriously marked with painful sacrifices, physical challenges, and, in some cases, profound loss. The purpose of a rite of passage, of course, varies depending on one’s age and circumstance, but I think it is fair to generalize that a rite of passage is primarily geared toward our need for creating (using modern psychological language) consciousness; consciousness about oneself, one’s place in the world, and about the world itself. In other words, to stay awake, to be aware, to see (inside and out)! And this kind of consciousness, as we know, is usually initially thrust upon us through painful severance, followed by a decent into those darker places. Rarely is consciousness something we choose! To confront one’s slippery shadow, blind judgments, and ultimately one’s death, all within a relatively short lifespan, is hardly a desirable undertaking. And yet, something in us gravitates toward the pull of initiation. In this regard, the function of a rite of passage is paradoxical: We inherently long for initiation, for consciousness, but would most likely avoid it we were conscious of the suffering and sacrifice it entails.

Stemming from my Judeo-Christian background, I often think of Job when contemplating a rite of passage. Here is an honorable man, who does all the “right” things, and he still gets slammed by God (or the forces of Nature, depending on your perspective). This cruelty seems like an unfair and gratuitous treatment of Job, but by the end of the story, not only is Job more conscious, humble, and wise, so is God. The story of Job is not your typical heroic quest story of good versus evil, but about Job’s surrendering to a way of being that is less ego-centric and more in tune with a humanness that is neither God nor animal, but somewhere in-between. For Carl Jung (2) , Job’s encounter with God is equivalent to a confrontation with the unconscious, a major aspect of a rite of passage, and the reason Jung can say, “God is the name by which I designate all things which cross my willful path violently and recklessly, all things which upset my subjective views, plans and intentions and change the course of my life for better or worse”(3) . I confess, when it feels as if I’ve fucked things up, which seems often enough, I find comfort in Jung’s words.

Due to God or Nature, life initiates us over and over again until we die. If consciousness is the propulsion behind initiation, then consciousness of our death is the final boon. As humans, we don’t live long. Not as long as a Bristlecone Pine, a Tortoise, or even a sea urchin. And, when we get sick or old or lose those we love, we can rest assured that we are never fully in control, but as compensation, we are given the most cherished of gifts, that of bearing witness. It is at this point that the potential for a rite of passage reveals itself, I think. And it can be heart-wrenching. The more we see the beauty of this world, and the deeper we fall in love, the greater, the sharper the loss. Consciousness can be a bitch. And yet, I don’t know anyone who would trade it in for anything less. It is an invitation to be fully alive.

Demeter and Persephone, Eleusinian Initiation Mysteries

I think this is a crucial point – that ultimately a rite of passage is not about fulfilling our greatest dreams or our fantastic potentials, but about decentering ourselves enough to see the world as it truly is. I imagine that in the old days, before artificial lighting and packaged food, our ancestors understood that if they became too self-absorbed, losing awareness of the world in which they lived, that they would perish. And this was true on both spiritual and literal levels, as there was no separation between higher and lower realms. The gods spoke in the language of rain, laughed in the blooming of flowers, exhaled with the migration of animals and birds, and rested finally in death.

Whether on a hunt, sitting atop a snowy mountain ridge, or in a hut deep in the forest, when the young initiate was taken out on their first big rite of passage, marking the transition into adulthood, they most inevitably met death in some form or another. Mircea Eliade, one of the foremost writers on initiation makes this point. Referring to the Wiradjuri children of Australia, he writes,

“For them, it [death] was an exterior ‘thing,’ a mysterious event that happened to other people, especially to the old. Now, suddenly, they are torn from their blissful childhood unconsciousness, and are told that they are to die, that they will be killed by the divinity. The very act of separation from their mothers fills them with forebodings of death – for they are sized by unknown, often masked men, carried far from their familiar surroundings, laid on the ground, and covered with branches.”(4)

It is impossible to get into the mind of a Wiradjuri initiate, to really understand what he or she feels and perceives, but I can do my best by paying attention to my own, albeit much less intense, initiatory experiences. For me, the initiatory encounters with death and loss have been a prerequisite for turning my focus toward the world. Death has forced me to ask, “What is my life about?” And almost immediately, my eyes open to a bigger realm that extends beyond myself. Meaning and purpose are found in service to that which is greater, which often lies beyond our knowing. As author Rebecca Solnit affirms in her remarkable book, “Hope in the Dark”,

“The belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterward either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone.”

To work on behalf of people we may never know, for a world we may never see, is truly an expression of an initiated adult. Such an attitude requires some consciousness of one’s death. For me, this has not been easy. And even after twenty years since my own first wilderness fast, I am just barely beginning to understand what this rite of passage business is all about. But it is comforting to know that there are others who have gone before. And although they are no longer among us in flesh, their work continues to guide and inform.

I wonder how things might look if we advertised wilderness rites of passage programs as ancestor preparation – that ultimately, we are preparing others and ourselves to be good dead people! Not only would this completely take us out of any possible commercial mainstream, it would highlight the seriousness and responsibility of our work as guides (in addition to providing some good humor, no doubt). When I think of Steven Foster, for instance, I think of a good dead person. I can’t say if he ever filled that void in his soul, or fulfilled his potential, but he is a damn good dead person. His spirit continues to guide and inform in ways known and unknown.

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

(1) Due to its connection to Native American Peoples the term vision quest is not used at School of Lost Borders. Nearly every culture practices, or had practiced, some form of rite of passage, but few are specific “vision quests”. For more, click see https://www.britannica.com/topic/vision-quest

(2) See C.G. Jung’s essay Answer to Job (CW 11)

(3) Cited in Edward Edinger, “The Creation of Consciousness”

(4) From Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth.

Posted in Uncategorized | 5 Comments »

In his oft quoted poem, “Don’t go back to sleep”, Rumi, writes, “The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you. Don’t go back to sleep. You must ask for what you really want. Don’t go back to sleep”.

For obvious reasons, this is a favorite poem among wilderness rites of passage guides, as a petition to the initiate to stay awake for an entire night whilst crying for a vision. If the initiate can bear the long and cold night, they are rewarded, at last, with the pink ribbon of dawn, a vision in itself, and the deep bodily knowledge that, even though the dark may feel like forever, eventually the light returns.

During this winter solstice season – the longest nights of the year – Rumi’s encouragement is more important than ever. How to stay awake through this interminable darkness when the temptation is to shut one’s eyes and drift?

This year, the dark fell particularly hard, when on November 8th I was co-guiding a women’s fast in one of Death Valley’s remote canyons. It was day three of the faster’s four day/night solo when I coincendently heard the news of the election results. Already the days were cold, the nights bearing a slight frost, but nothing prepared me for this chill. Like broken ice, a small fissure spread through the ceremonial barrier of non-space and time. The world rushed in with wild force.

And my thoughts rushed out, just as quickly. Thousands of people, I was certain, were on the streets protesting, doing important work, while I was isolated in the far reaches of the desert. All I could hear was silence, save one lone owl in the night. The peace of wild things didn’t jive. How was I going to hold this so-called sacred, yet broken, container for the next week?

Two days later, our fasters returned from their solos, exhausted but glowing like newborn babes. After our traditional celebratory breakfast, we gathered in a circle and my co-guides and I told them the news. Better to let everyone know while still together than later when all scattered about. But after the exuberance of having just completed the solo ordeal, it wasn’t so easy to distribute this dark truth of the world. And yet, the truth of the world happens all the time, whether we hear it or not. Political decisions are made, people suffer, oceans rise. This time, the world just came in sooner, harsher, and colder than usual.

It was a very painful but remarkable experience to share the election news in this way. Like opening Pandora’s box, I could feel the darkness escape into our circle in the form of despair. Sure, we all know that climate change is destroying our planet. That species are continually going extinct. We know people die every second of every day. And ultimately, we know, death will come for us too. But at this particular time and in this place, such realities became flesh, the taste of their blood lingering in our mouths. Some of our group cried and expressed loud disbelief and shock. Others became silent like the empty night – the night that feels like forever. All were courageous.

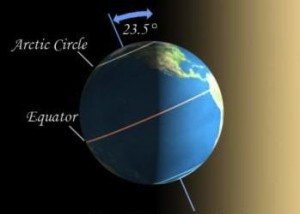

Now, nearly two months after the election, on this solstice eve, I remember – yes, I remember! – the sun never stands still. As it approaches its zenith, it slows to a near halt, but only for a pause. An in-breath. And then on the out-breath it turns and slowly makes it way back home.

Having once stayed up all night long, I’ve had a vision. It is a distance one now, one I easily forget, but I know, deep in my bones and in the center of my heart, that no matter how long the night may seem, the sun returns. It really and truly does. I don’t believe this. I know.

Rumi’s words ignite sparks. I used to think of his poem as kind of quaint. A gentle encouragement to try out an all night vigil. Take it or leave it. If you fall asleep, fine. But now, I read Rumi’s words with more attentiveness, as a call for intense awareness. Living beings are dying. Don’t go back to sleep. Death is always nearby. Don’t go back to sleep. Ask for what you want. Don’t go back to sleep.

And the secret?

Listen carefully. The sun will rise again. And not even a man who calls himself president

can stop it.

The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you.

Don’t go back to sleep.

You must ask for what you really want.

Don’t go back to sleep.

People are going back and forth across the doorsill

where the two worlds touch.

The door is round and open.

Don’t go back to sleep.

~ Rumi translated by Coleman Barks

From Essential Rumi

Posted in Uncategorized | 4 Comments »

I’ve spent a lot of glorious time in the California Sierra this summer (meaning I didn’t do much writing) so intead of posting something new, I am posting this older piece I wrote for the journal Psychological Perpsectives, which is published by the Jung Institute of Los Angeles. It’s a very long piece for blog standards, but there are some jewels to be found within. This is the pre-reviewed version. For the offical published version please refer to Psychological Perspectives issue 51-1, published in 2008 and available online at available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/00332920802031904

Climbing the Alchemical Mountain: A Woman’s Story of Initiation

“There is a mountain situated in the midst of the earth or center of the world, which is both small and great. It is soft, also above measure hard and stony. It is far off and near at hand, but by the providence of God invisible. In it are hidden the most ample treasures, which the world is not able to value”.

– Thomas Vaughan, “Allegory of the Mountain” (1651, online)

Thomas Vaughan, the seventeenth century mystic, likens the alchemical process to a journey to a mountain. Vaughan never explicitly states what the mountain represents; rather, he leaves it up to the reader to discern its meaning. Such secreted, but guiding principles, are not uncommon to the mystic traditions. The “treasure that is hard to attain” can only be found by making one’s way through the labyrinth of paradoxical and puzzling messages – “both small and great, soft and hard, far off and near at hand.” Alchemy is hardly a flatlander’s proposition, horizontal and predictable. It is more like a narrow path that winds up the mountain, circumambulatory, full of unexpected twists and turns. It is only by the guiding presence of desire, a pure heart, and complete grace that one may discover this path.

On the other hand, it is no mystery why Vaughan chose the mountain for his allegory. Simply by their verticality, height, and inaccessibility, mountains evoke fear and awe. There are no shortages of extremes here. No lack of blizzards, thunderstorms, and avalanches. Mountains are radically high and low, hot and cold, beautiful and terrifying, and entering into this landscape can fill a person with both anticipation and a great deal of anxiety. And yet, despite all fear, many of us have dreamt about the treasure hidden within the mountain. To even speculate about gold – “the treasure that is hard to attain” – is a tenuous endeavor. How does one find that which cannot be seen? How does one seek that which is unknown? To seek the treasure in the mountain is like a fish seeking the sea, a bird seeking air, the ego in search of the Self. “We do not know it, we can never know it, because it is the bigger circle that includes the smaller circle” writes Jung (1976, p. 296). And rightly so, as the alchemist writes, it is “invisible.”

So, we look for traces…a little gold dust gathered around a fissure… a dream, a fantasy, a symptom, a sparkle of beauty in an inhospitable world….

And for me, such traces are often discovered within the natural world, which, in this case, is the Sierra Nevada, California’s gold country. And, although I use no pick, shovel or pan, discovering the beauty and intensity of this mountain range has, indeed, sparked my interest – a small claim on psyche, so to speak. To see the crystalline peaks reflecting brilliantly in the sun only confirms my intuition that, yes, there is gold in these hills. The perpetual snowfields, hardened into milky blue glaciers, speak of eternity, a time when the world was preserved in ice. Up here time is non-existent. But only a few feet below I can hear the trickle of running water. The melting of eternity sustains life.

As a manifestation of the Holy Other, mountains emanate a power that awakens a sense of the sacred. No human-made temples can match mountain splendor. No cathedrals can lift one’s heart and mind with the same reverence. Mountains are nature’s temples, constantly turning our gaze upward, toward sky, stars, sun and moon. I have seen how the fiery presence of the alpine glow reflected in the immeasurably deep glacier lakes – rubies and emeralds swirling inside/outside of each other – inspires the remarkable artistry of stained glass. And, how the soft glow of the moon upon the sharp, serrated peaks hangs like a candelabrum over the trees that stand reverently like parishioners in an ancient gesture of observance. And, the flowers – Leopard Lilies, Crimson Columbines, Indian Milkweeds, Snow Plants, Bleeding Hearts, Shooting Stars, Pride of the Mountains, Wild Irises, and California Fuchsias – alter pieces and offerings. If there is such a thing as sacred space, mountains are the birthing spot.

The Approach

“To this Mountain you shall go in a certain night – when it comes – most long and most dark, and see that you prepare yourselves by prayer. Insist upon the way that leads to the Mountain, but ask not of any man where the way lies. Only follow your Guide, who will offer himself to you and will meet you in the way”.

— Thomas Vaughan, “Allegory of the Mountain”

Traveling along the Eastern edge of the California Sierra Nevada, it is impossible not to notice the mountains that rise above the valley. There is no mistaking Mount Whitney, for instance, at 14,494 feet, saw-toothed and shadowing the small town below. And across the valley, at 14,246 feet, stands White Mountain Peak weathered and bald like an old saturnine god. The word “mountain” is rooted in the Latin word, ē-minēre, which means to stand out, to project, and to be eminent. Whether it is Whitney, White Mountain, or Everest, one obvious truth stands out…mountains don’t hide.

But according to the allegory, the mountain that contains the “most ample treasures” “by the providence of God is invisible.” Furthermore, finding this mountain is a quest that can only be undertaken during the “most long and most dark” night. At first, such statements are perplexing. How can we see that which is invisible? And why must we travel through the dark? Everything that seems to be true about mountains – high, clear, and sunny – stands in opposition to that which is invisible, hidden, and dark.

Obviously, two different mountains are being discussed here: one that is external and concrete, and the other that is imaginal and symbolic of an archetype. But, philosophically speaking, at what point do we differentiate between the concrete and the archetypal? Everything that I sense about mountains – high, vertical, beautiful – echoes with archetypal imagery. Conversely, when I consider Mountain Archetype, my mind’s eye spontaneously envisions a snow-crested peak piercing through a crown of clouds. Such an image fills me with reverence and fear. My very real self is affected by the image.

Such speculations would have been pointless in pre-modern society. The ancients made no distinctions between the external and internal realms. Nor did they maintain abstract notions of an individual, psychological state of mind, as we understand it today. Rather, that which we today commonly refer to as the inner realm of the unconscious, in antiquity was known as the underworld. Only after years of philosophical and scientific development did the underworld evolve into the innerworld. But, perhaps, we are not so far removed from our pre-modern ancestors as we initially think, for the unconscious is still referred to that which is below, dark, mysterious, an often terrifying abyss.

Furthermore, the ghosts and spirits of the underworld continue to haunt us in the form of symptoms and complexes. They enter our dreams. They act on us in mystifying ways. When the allegory informs us that we can only seek the mountain during the “most long and most dark” night, without doubt, we are being summoned to the underworld unconscious.

It is no coincidence; therefore, that right as I began writing this piece about the mountain, the following dream came to me…

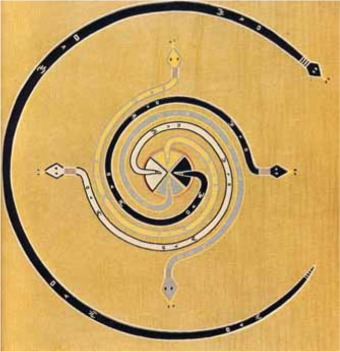

I am in my apartment when, suddenly, I hear a loud siren. Looking out of my window, I see a large passenger jet heading toward me. In fear, I watch the jet crash on my roof, at which point, it transforms into a large serpent! The fuselage of the jet becomes the serpent’s head and the cockpit becomes the tail. I have a jet sized, urobouric serpent sitting on my roof, slithering and devouring.

In the days that followed this dream, my endeavors to write turned into frustration. Clear thoughts sank into confusion, and for many days I sat at my desk paralyzed by anxiety and fear. It was if the sun descended, and the mountain, of which I was so eager to explore, faded into the dark. All paths disappeared.

Jung points out that when one tries to go the way of consciousness, the instinct will emerge. Thus, it is not unusual that the slithery serpent of the underworld would appear just as I was ready to approach the mountain. Attempting to climb, made conscious by writing about the mountain, the serpent in me was stirred from her slumber. Detecting my desire to ascend, feeling the earth vibrate beneath my steps, she crept up from beneath the mountain, grabbed me, and pulled me under. Such an attack melted me; all my mental capabilities became a dark mush. Clarity turned obscure. Light became dark. Everything that I imagined these serrated peaks to resemble – sharp and differentiating – have only served to cut deeper into the unknown underworld.

“When you have discovered the Mountain the first miracle that will appear is this: A most vehement and very great wind that will shake the Mountain and shatter the rocks to pieces. You will be encountered also by lions and dragons and other terrible beasts; but fear not any of these things. Be resolute and take heed that you turn not back, for your Guide – who brought you thither – will not suffer any evil to befall you. As for the treasure, it is not yet found, but is very near”.

— Thomas Vaughn, “Allegory of the Mountain”

The struggle between consciousness and instinct is real, as it is ancient and archetypal. This conflict is often retold in stories of young initiates who, upon climbing a mountain, are deterred by threatening serpents or dragons that guard the treasure. If the initiate successfully subdues or conquers the instinctual dragon, he is then free to climb the mountain and toward the treasure of greater consciousness. This is never an easy task, and not to be taken lightly. “Taoists stress the dualities, the dangers even, of climbing a mountain without training oneself through spiritual exercises. Mountains are sometimes inhabited by fearful beings who bar all approaches to the summit” (Chevalier J. & Gheerbrant, 1969/1996, p. 680).

1370-1371CE, Islamic, taken from the Archive for Reseach in Archetyapl Symbolism (ARAS)

In medieval Europe, upcoming kings were expected to venture into the mountains, brave a dragon, and make their way back safely to the foot of the mountain. So seriously did Medieval Europeans take the threat of dragons that some scholars devoted themselves to dracology, the scientific study of dragons.

As a sign of their diabolical contamination, mountain ranges like the Alps were thought to be densely infested with dragons. As late as 1702 Johann Jacob Scheuchzer, a professor of physics and mathematics at Zurich University and a correspondent of Isaac Newton, collected evidence of dragon sightings, canton by canton, into a comprehensive dracology. (Schama, 1995, p. 412)

And certainly, serpents and dragons have not escaped modern consciousness, although they now appear in new guises such as weapons of mass destruction or other war machines. Just as in the days of old, we continue to search for these elusive creatures in the mountains and caves of foreign lands not realizing they exist right here at home, within ourselves. Hopefully, our dragons of instinct will not become dragons of extinct.

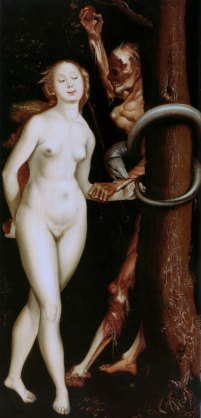

In Western religious history, the serpent/dragon is almost always associated with the feminine, which in Western tradition is symbolized by the figure of Eve. As narrated in the book of Genesis, Eve did not conquer the serpent, but rather, she was seduced by it. And, in doing so, she jeopardized the spiritual status of all humanity. Symbolically, Eve finalized our mortality. She gave flesh to spirit. “The spiritual man was seduced into putting on the body” writes Jung (1954/1967, p. 94). According to the Gnostic tradition, it is through Eve – the feminine principle – that we – our souls – are seduced away from the heavens and birthed into this temporal realm of life on Earth. For this reason, Neumann (1994) points out, “The emergence of the Earth archetype of the Great Mother brings with it the emergence of her companion, the Great Serpent” (p. 197).

Han Baldung Grien, c1530.

On the other hand, it’s no surprise that, at least in the Christianized West, Eve and the serpent are regarded as evil. Who wants to be human? Who wants to suffer an earthly fate? Who wants to face the onset of age, the frustration of physical limitations, and death? Every attempt to escape humanity is contempt for Eve. Every effort to cast off mortality is to tread upon the serpent. And, despite my own ambivalence about life and death, the serpent of my dream has thrust me back into the Garden and set me face to face with this feminine principle. For, if to climb is to meet God, the first God we encounter is the dark one – Magna Matter – she who is coiled in the great chasm of creation, dressed in dark earth, upon whose very back we attempt to climb. Alas! The mountain!

In alchemy, the serpent is often regarded as a symbolic manifestation of the prima materia, that shadowy and slippery aspect of the unconscious, which includes all that we deem evil and repulsive in ourselves. Consider the serpent – cold blooded, hairless, legless, belly on ground. To encounter a snake whether in nature or in dreams almost always triggers a gut level reaction. After all, the bowels are their territory. Such instinctual energy not only fuels our impulse toward consciousness – the energy needed for the climb – but also our most reactive, habitual, and self-destructive human natures, which most of us would rather leave hidden, invisible, buried deep beneath the ground. Such a landfill is that upon which our glorious mountain stands.

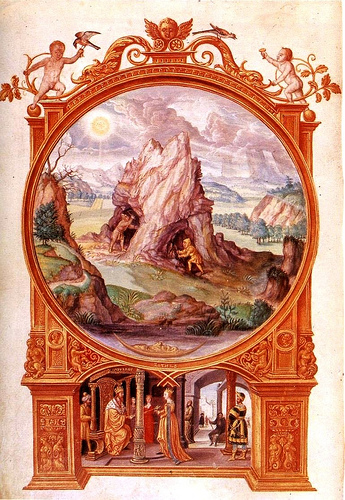

Splendor Solis, extraction of the prima materia

Jung (1958/1968) writes, “The prima materia comes from the mountain. This is where everything is upside down: ‘And the top of this rock is confused with its base, and its nearest part reaches to its farthest, and its head is in the place of its back and vice versa’” (p. 433). And, truth be known, the only way up the mountain is through the mountain. The path to consciousness leads through the prima materia. Such a detour is hardly welcomed by those who desire a quick route to consciousness. Here, all is dark and disorienting. There are no distinctions. There are no clear-cuts, no roads to differentiate one side from the other, no demarcations between the concrete mountain and its image reflected in the shimmering lake below. That which appears solid and unchangeable in the light of day becomes ephemeral at night. The sun submerges into the lake. A breeze slips beneath the evaporation of day. A chill drops in. Everything changes. Ashen mountains turn red to purple to blue, and finally to black.

There are many myths that speak about the “long dark night of the soul” – the encounter with the prima materia – but, at this juncture, I bend my ear toward the cries of Persephone. Perhaps, on the outset, it appears that the Demeter/Persephone myth has little to do with mountain landscape, and yet, it is so intricately tied to mountain consciousness. “Demeter and Kore, mother and daughter, extend the feminine consciousness upwards and downwards …. and widen out the narrowly conscious mind bound in space and time …. ” writes Jung (1951/1969, p. 188). As told in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, the innocent maiden, Persephone, is in a field where she finds a splendid flower that impresses even the gods. Dazed by the beauty of the flower, she reaches down to pick it or to gaze in wonder at it. Suddenly, the earth opens up and Hades emerges on a chariot and abducts Persephone into the realm of the dead where he rapes her and makes her his wife. By the efforts of her mother Demeter, Persephone is eventually brought back to the realm of the living. Her death and rebirth is simultaneously a descent and an ascent (1).

The Rape of Persephone, Rembrandt, 1631

Elaborating on the rape of Persephone, Helen Luke (1990) writes, “The moment of breakthrough [of consciousness] for a woman is always symbolically a rape – a necessity – something which takes hold with overmastering power and brooks no resistance” (p. 56). Here, it is helpful to keep in mind that, as with all myths, each character and theme in the story is a manifestation of a preexisting archetype. This is not about rape in the literal sense, which is violent, harmful, and downright wrong. Persephone’s rape is a symbolic expression of the archetype of initiation, which always involves an encounter with the overmastering power of instinct. Furthermore, that which at first feels like an attack from the outside is later discovered within oneself. In other words, Persephone is taken by her own instinct. Essentially, she rapes herself. She ruptures her own innocence because deep down she knows that the sacrifice of innocence – that unconscious state of passivity – is a fundamental aspect of being a complete woman.

The myth of Demeter and Persephone also sets the stage for the Eleusian initiation rites, which were practiced for thousands of years in ancient Greece. The ritual involved a reenactment of the Demeter/Persephone story: Persephone’s abduction, rape and marriage to Hades, Demeter’s grief and her search for Persephone, and finally, the reunification of Demeter and Persephone. The ritual came to a peak when, in the dark temple of Eleusis – a symbol of the underworld – the Hierophant revealed a mown ear of corn to the initiate as a symbol of divine wisdom and immortality.

Demeter and Persephone in the Temple of Eleusis, Classical Greek Era

It is beyond the scope of this article to even touch upon the multiple dimensions of the Eleusian Mysteries, but it is important to understand that the rites involved honoring and sustaining the feminine mystery of death and regeneration as an on-going cycle of nature. Demeter and Persephone are so inseparable within the collective unconscious that they can be considered to be one in the same, or rather, two opposites of the same pole – life and death. Demeter, as goddess of the upper-world, is the mother of life, whereas Persephone, as goddess of the underworld, is the queen of death (2).

“A daughter with the name of “Mistress” or “She who is not to be named” was born of this abduction. The goddess becomes a mother, rages and grieves over the Kore who was ravished in her own being, the Kore whom she immediately recovers, and in who she gives birth to herself again. The idea of the original Mother- Daughter goddess, at root a single entity, is at the same time the idea of rebirth” (Kerenyi, 1969, p. 123).

Persephone’s descent into the underworld is a return into the chthonic womb of the Great Mother – the vagina dentata. Having been severed from Demeter, Persephone enters the greater mother and the womb of her second birth. And thus, from here on, Persephone is my guide into the cavernous mountain, while her mother, Demeter, is the mountain into which I return. Having followed the footsteps of Persephone, I enter the womb of the second birth.

The Ascent

“After this wind will come an earthquake that will overthrow those things which the wind has left, and will make all flat. But be sure that you do not fall off. The earthquake being past, there will follow a fire that will consume the earthly rubbish and disclose the treasure. But as yet you cannot see it”.

— Thomas Vaughan, “Allegory of the Mountain”

Looking at the California Sierra Nevada from the east, it is easy to observe how this huge segment of the earth’s crust has been broken loose and pushed up, giving the mountain range a westward tilt. The eastern slopes are dramatically steep and rugged, and peaks such as Mount Whitney, Williamson, Pinchot, Birch, and Kearsarge rise up like great waves, inducing a delightful terror. “Climb, climb, climb,” they cry out, “but only at your own risk.” No guarantees of safety. No promises of comfort. No assurances of ease. Despite all the warnings, these mountains beg to be climbed. It is never a question of why; it’s always a question of how.

And for months I have been asking myself, “How?” How do I get out of the mountain so that I can begin to climb the mountain? How do I deliver myself from the womb of dark Demeter? Alchemically speaking, how do I free my spirit from the bedrock of matter? I have been groping for practical advice…. give me some instructions, a “how to” manual for climbing. In desperation, I have cried out for answers. I have scoured through my books seeking a solution. I have consulted friends, therapists and mentors…all to no avail. For the first time in my life, I realize that there is nobody out there who can help. Like the Eleusinian mysteries, the alchemical work of inner transformation is shrouded in secrecy. It cannot be spoken…only experienced. Casting aside books and counsel, I’ve had to experience that which I initially set out to write, an experience that is beyond rational explanation.

In addition, the mystery, like pregnancy, unfolds at its own pace; impatience does nothing to further the process. At first, we may assume that if we just work hard enough, or fast enough, or engage in enough therapy, or whatever self-help discipline we choose, we could put an end to this dark business and get on with climbing. The alchemists stressed the dangers associated with haste,

“He who is in a hurry will complete his work neither in a month, nor yet in a year; and in this Art it will always be true that the man who is in a hurry will never be without matter of complaint”. (cited in Edinger, 1985, p. 5)

Helen Luke (1989) points out that haste is an act of insubordination, “the original sin from which the disobedience sprang was haste, and that the knowledge of evil was not in itself forbidden. ‘I must have what I want now.’ Haste is born with the ego’s consciousness of time” (p. 181). In its original meaning, the word haste refers to violence, fury, struggle, and strife. It is in our haste that we resent the Great Mother for keeping us down. It is in our haste that we kick against the womb. Like a child screaming, “let me go,” we are constantly fighting to free ourselves as hastily as we can. But, haste has no place in Hades. Nonetheless, the timeless quality of the underworld is not an easy thing to endure. As Jung writes,

“The ego idea, for example, would be to say: “there is a good thing on top of that mountain. I will make a straight line for it.” but the archetypal way is not like that; it is a serpentine way that wiggles and spirals its way to the top. We often feel defeated by it and brought to a standstill. It makes most people terribly impatient and even desperate when nothing happens and they get nowhere. They feel hindered all the time; they don’t understand that this is just as it should be, that it is actually their only chance of getting to the top” (1976, p. 295).

Once again, the alchemical mountain presents us with a paradox; namely that, although haste results in struggle and strife, one cannot expect to reach the peaks without some element of haste. Even the alchemists exhibited a desire to hasten the earth’s natural, but much slower, process of turning ore into gold. Pressure, exertion, and attention are necessary to heat up, and intensify the process. Like climbing, it entails going up and against gravity; we go against nature.

Psychologically speaking, the work involves going against our nature. That which we desire the most is often the very thing we suffer from. To struggle against our desires is to go against our very nature, while at the same time, it reunites us with Nature. In other words, when we suffer from unmet desire, the ego becomes active. It knows that it wants something, and this something is hidden within the core of the unconscious. It is only through unwavering desire that we become aware of the true nature of the unconscious. It is only through a desire to climb that we realize there is a mountain to climb in the first place.

And nothing makes a person more real, more palpable, and more solid than unmet desire. When we suffer from desire, the Self is embodied through us, we exist, and etymologically, to exist means to stand still. To stand solid like a mountain. Persephone, in her suffering and despair, is in the process of becoming real…as real as a mountain.

Mountains standing close together:

The image of KEEPING STILL.

Thus the superior man

Does not permit his thoughts

To go beyond his situation.

– The I Ching (cited in Wilhelm, 1988, p. 86)

Eureka Valley Sand dunes…

Tonight I walk in the dark. There is a sliver of a moon illuminating the south side of the dunes, while the north slopes are left in the dark, creating a strange mix of blackness and translucent moon glow. It all feels a bit lunar and mysterious. Without thinking, I start trekking up the sand dunes. I feel an urge to climb as high as I can. The sand dunes are over 680 feet high, making them the tallest in the United States.

Reaching a small plateau, I look up and notice a gaping black hole in the sand above me. My heart sinks. It looks like death. Maybe if I climb into the hole, I will conquer my fear of death. Maybe if I climb into that hole, I will gain the “secret.” I continue to climb the sandy terrain. Sweaty and thirsty, I imagine myself as Jesus walking through the desert of temptation and the devil appears as a snake. “Sssssso”, says the snake, “You want to get to the top?” And, yes, I am tempted. I Want. I Desire. I AM. I am tempted to reach the heights. I am tempted to see God.

Now the dunes are very steep and I resort to hands and knees, plodding to the peak, sinking in the soft sand, groping in the dark. I think the top is near, but I can’t make it out against the black sky.

Suddenly, I hear a deep vibration emanating from beneath the dune. At first, I think it is the sound of a jet echoing off the sand, but as I continue to climb, the vibrations become louder. Eventually, the entire dune begins to vibrate with a loud deep booming sound. Stricken with fear, I freeze! The vibration subsides, but as soon as I resume climbing, it returns. I imagine a great avalanche burying me deep in the sand, and in my panic; I run! As I leap down the dunes, the impact of my body makes the vibrations increase in volume. I freeze again. Very slowly, I make my way to the base of the dune where I give way and begin to weep. Now, I know what it is like to see God. It is terrifying.

Not until later did I learn that the booming dunes are a natural phenomenon, which occur only in the highest and driest of sand dunes. According to ancient myth, a great sea monster is buried in the dunes. Longing for her mate, she rumbles and moans, she twists and turns. As for me, I got a terrifying taste of the Great Mother. Like Persephone, I felt the earth opening up, and I imagined myself buried alive in thousands of feet of sand. And so, I ran. And in my flight, I felt utter defeat.

Soon after my encounter with the sand dunes, I began to imagine that the vibration was Demeter in the throws of labor, and that, this time, it was I who was being born. Helen Luke writes, “Without terror, without experience of the terrible face of God, there can be no divine birth” (1990, p. 67). This newborn woman is no longer an innocent Persephone, ghostly and anima-like. Rather, she carries within her the horrifying and awesome mystery of life and death, she is, in herself, the alchemical vessel, the womb of transformation. Such an experience taps into the great Eleusinian Mystery, “By touching a reproduction of a womb, the initiate evidently gained certainty of being reborn from the womb of the Earth Mother and so becoming her very own child” (cited in Kerényi, 1967, p. 106). Here the innocent is swallowed alive by the unconscious, digested, and, having acquired the secrets of “matriarchal consciousness”, is birthed anew. No longer just a daughter of Demeter, no longer just a wife of Hades, but a woman who is both Demeter/Persephone – human and divine, mortal and immortal. Darkly divine. To enter into, and emerge from the mountain, is to be born again.

The Peak

“After these things and near the daybreak there will be a great calm, and you will see the Day-star arise, the dawn will appear, and you will perceive a great treasure. The most important thing in it and the most perfect is a certain exalted Tincture, with which the world – if it served God and were worthy of such gifts – might be touched and turned into most pure gold”.

— Thomas Vaughan, “The Allegory of the Mountain”

The Sierra Nevada mountain range is one of the most distinctive topographical features in the State of California. To see these mountains from above gives the impression that God with an enormous hand pinched the center of the state to form these raw, serrated edges. This divine study in clay and stone has evolved into the central nervous system of the state, for without it California would not have the water supply it needs to sustain its population. The white snowy peaks of the mountains indicate that the source of all life – water – has its beginning in a very mysterious and, somewhat, indifferent, place. To step into this realm of ice-aged glaciers is to enter timelessness…only the movement of water serves as a reminder that in the midst of eternity, change is constant. Undeniably, we are profoundly dependent on the quiet melt of snow that slowly seeps beneath these highest rocks …

I promised myself that I would return to the mountain before this week was over. I walk up the wash to the lovely mountain range on the northern end of the valley. I hope this re-visit will shed some light on my defeat. My fear of the sand dune continues to surge through my nerves, and I am beginning to think that I will never reach the top of the mountain. Now, standing at the base of the mountain, looking up, resigned…. I ask, “So, what shall we do now?” And, in my imagination, I hear the mountain respond, “Sit down and don’t climb.” “Sit down on the soft sand, feel the warmth of the sun, and simply look at me.” I feel relieved of the burden of climbing. I sit in the wash with my back against a warm rock, sheltered from the wind, resting at the foot of the mountain. Waiting, musing, and sketching circles in the sand with the tip of my finger, a prayer spontaneously enters my thoughts, “Hail Mary full of Grace the Lord is with Thee. Blessed are you among women and blessed is the fruit of your womb Jesus….” The phrase repeats itself over and over…“Hail Mary full of grace.”, “Hail Mary full of grace”, “Hail Mary full of grace.” How strange that these words should come to me. I wasn’t raised Catholic, this prayer has meant nothing to me. But, now it makes perfect sense. Grace is the water that flows from the mountain.

Grace is divine intervention, bestowed at the crucial moment of defeat and despair. Grace is given freely and is not based on merit. It cannot be earned. And thus, it transcends the ego. Simply put, grace makes no rational sense. It just is.

Like a cool steam; grace flows from the mountain. Only grace can move that which is hard and permanent. Only grace can soften a rigid ego, erode stone, and bring forth new life. When the waters of grace break open, new life gushes forth. It is no coincidence that the Eleusinian rites ended with a ritual of pouring water, a symbol of the living water and eternal life. This eternal water is what the alchemists call divine Wisdom or the aqua permanens. “Gideon’s dew” is a sign of divine intervention, it is the moisture that heralds the return of the soul” (Jung, 1946/1966, p. 279). Or, as the Zen master, Dogan writes, “There is walking, there is flowing, and there is a moment when a mountain gives birth to a mountain’s child” (cited in Tanahashi, 1985, p. 103).

The alchemists recognized the necessity of grace for the completion of their work, and, most likely, found grace to be an integral aspect of the treasure.

“Therefore, if any man desire to reach this great and unspeakable mystery, he must remember that it is obtained not only by the might of man, but by the grace of God, and that not our will or desire, but only the mercy of the Most High, can bestow it upon us”. (cited in Edinger, 1985, p. 5)

From a depth psychological perspective, I imagine grace as being what Jung termed the transcendent function. Jung noticed that when the tension of the opposites is held long enough, when one feels as if they are at the moment of psychological death, a third, previously unimaginable possibility emerges. A new image is spontaneously created by the psyche. Although this may sound abstract, the experience is highly numinous. It is like being cooled with living water. It is an act of grace.

Perhaps, it is difficult to imagine Persephone’s rape as an act of grace, but certainly her last minute decision to eat the pomegranate seed is. At the moment when she is about to leave Hades, she eats the seed, and thus, has to repeat her underworld descent every winter. Did Persephone understand the consequences of eating? Did she know that underneath her conscious yearning to return to her mother, that she really didn’t want to return to her previous state as innocent daughter, to remain incomplete, separated from her own feminine nature? As Luke writes, “This is an image of how the saving thing can happen in the unconscious before the conscious mind can grasp at all what is going on” (1990, p. 65). By sheer grace, Persephone swallowed the dark seed of Hades, which has taken root and sprouted a new personality. What was just a tiny seed has blossomed into a full-grown woman. What was simple beauty on the surface has become dark beauty below.

Persephone, Queen of the Underworld, Greek vase

For a woman, becoming real – ontologically real – is what the Demeter/Kore myth is about. It is not about conquering fears, over-coming obstacles, slaying the dragon, or reaching the top. It is about entering into the mountain of the Great Mother – the mountain of all mothers – and reclaiming the power of instinct that has sustained life, and accompanied death, throughout the ages. When a woman recognizes that she comes from Mother, is mother (even if not literally a birth-mother), and is the container of the great mystery, symbolized by the mountain on which she stands, she becomes complete: virginal and sexual; able to love freely, rather than from a place of inner deficiency. She becomes, as Esther Harding writes, “one-in-herself.”

“She does what she does – not because of any desire to please, to be liked, or to be approved, even by herself; not because of any desire to gain power over another, to catch his interest or love, but because what she does is true”. (1971, p. 125).

To be “one-in-herself” is not an abstract theoretical idea. Practically speaking, it means that a woman is not dependent on another – whether externally as in a human relationship, or internally as the animus – to dictate her self-worth. For me, this means that it is no longer necessary to reach the peaks in order to justify my existence. I no longer need to climb to prove my worth to society, to others, or even to myself. Rather, I climb the mountain because I want to. It is what is true for me. The opus is not the attainment of perfection, but the acceptance of completeness. To reach the peak of the mountain is not a conquering. It is a gift.

And, for me, no landscape is as mysterious and stunning as the high country of California Sierra Nevada. This is the land of the great wise ones – grandmothers and grandfathers – manifest in granite batholiths, 65 million years old, which have risen to their zenith. Here we reach the limits of life where oxygen is thin, the sun is intense, freezes are long, and winds are strong. This landscape points to that which is eternal, to a “oneness of things beyond” (cited in Killion, 2002, p.18). Old mother earth unveils her soiled robe, and exposes her overwhelming brightness, no longer seen as condemned Eve, but as Sophia, the wise goddess of the mountain.

In the Gnostic tradition, there are two personifications of Sophia, upper and lower. The lower Sophia is the one who fell from Heaven and into earth. Seduced by the serpent, she is the dark one who lives in the mountain, animating all of creation. She is the vibration that rumbles beneath our feet. For this reason, the alchemists perceived her, and her consort the serpent, as a somewhat complex and symbolic form of primordial spirit – serpens Mercurii, the earth spirit, or anima mundi.

Anima Mundi-Thurneisser zum Thurn (1574) from Jung, Psychology & Alchemy, p. 189

In her higher state, Sophia is the wisdom of God. Sophia, the Greek word for wisdom, is the guide and the goal. Without the grace and wisdom of Sophia, God’s creation is nothing but dead matter. God may have the power to create mountains, but Sophia has the power to give them life. It is difficult to understand the higher and lower aspects of Sophia in purely abstract terms. It is much easier to imagine her by way of metaphor, perhaps as a glacier, overwhelmingly bright in the sun, but also as cool water that melts and descends from the mountain, providing life to all that is below. Jung writes,

“The wisdom is the nous that lies hidden and bound in matter, the “serpen mercurialis” or “humidum radicale” that manifests itself in the “viventis aquae fluvius de montis apice” (stream of living water from the summit of the mountain). That is the water of grace, the “permanent” and “divine” water which “now bathes the whole world”. (Jung, 1954/1969, p. 236)

Such wisdom enters into our lives in strange and paradoxical ways. For instance, I know that wisdom is not knowledge attained by books. On the other hand, having an inquiring mind is essential to finding her. I know that wisdom cannot be achieved by human will alone, but wisdom doesn’t come without continual effort. Although wisdom is a gift of grace, it is discovered through a great deal of painful struggle.

Perhaps, wisdom is an indescribable knowing that comes by way of Persephone and her passage through desire, suffering, defeat, and finally to grace. Desire is the fire that burns deeply within us, and in our incessant attempts to fulfill our desire we suffer. And when we can no longer bear the burning of suffering, we experience defeat, which naturally ushers in the waters of grace. Perhaps, knowing the mystery and paradox of the natural unfolding of individuation – desire, suffering, defeat and grace – is wisdom.

Ultimately, wisdom is Demeter and Persephone, the higher and lower Sophia, reunited as “one-in-herself”. The transcendent realm of Persephone touches the material world of Demeter. Matter becomes meaningful. The woman, now goddess and human, becomes the queen of the secrets of domestic life – not in the traditional sense, but as the great woman – and the one who brings the power and wisdom of creativity into the material realm of ordinary life.

The Return

“This Tincture being used as your Guide shall teach you and will make you young when you are old, and you will perceive no disease in any part of your bodies. By means of this Tincture also you will find pearls of an excellence which cannot be imagined. But do not you arrogate anything to yourselves because of your present power, but be contented with what your guide shall communicate to you. Praise God perpetually for this His gift, and have a special care that you do not use it for worldly pride, but employ it in such works as are contrary to the world. Use it rightly and enjoy it as if you had it not. Live a temperate life and beware of all sin. Otherwise your Guide will forsake you and you will be deprived of this happiness“.

— Thomas Vaughan, “Allegory of the Mountain”

So, what is the Tincture, or the “treasure that is hard to attain?” It is impossible to define the Tincture, but we know from the allegory that its purpose is healing; both personally and collectively, however this healing may appear. Jung (1977) writes, “The opus magnum had two aims: the rescue of the human soul and the salvation of the cosmos” (p. 228). Individual healing is linked with universal healing – the microcosm and the macrocosm are interdependent. I am certain that the healing tincture is not a static and concrete thing, but rather like wisdom, it is mercurial, provisional, changing and alive. Perhaps, it is even ourselves – women and men – having descended into the mountain underworld and recovered the life giving power of wisdom.

Without divine wisdom the world becomes a “nothing but” world. Nature is nothing but dead matter. Our lives are nothing but mundane. Our desires are nothing but infantile. Our creativity is nothing but whimsical. And, we are now witnessing a world that is suffering from a “nothing but” drought of wisdom. Certainly, we have seen progress and development in areas such as technology and science, which is comparable to the success of mountain climbing, but such achievements often lack the life generating creativity of feminine wisdom. We are standing on the mountains of our own making, and as a result, we are on the brink of ecological and cultural disaster.

Creativity is the antidote for a dying world. As Jung points out, “The creative activity of imagination frees man from his bondage of ‘nothing but …’ ” (Jung, 1931/1966, p. 46). To create is to make the imaginal real. With our own hands and hearts, we mold our dreams and give them life. We sing, dance, cook, move, sculpt, paint and play our lives into being. Such creativity is not always sweet and pretty. The serpent is still a serpent. Unfortunately, there have been many cultural misunderstandings regarding this creative instinct as having no relationship to wisdom. Thus, it is easy to misinterpret the serpent/dragon-slaying hero myths as the need to suppress instinct, as opposed to befriending it for the sake of creativity. As the earliest religions demonstrate, the instinctual serpent is not, in and of itself, evil, but rather, the source of imagination and healing. Chickasaw poet Linda Hogan writes,

“Before the snake became the dark god of our underworld, burdened with human sin, it carried a different weight in our human bones; it was a being of holy inner earth. The smooth gold eye, the hundred ribs holding life, it coiled beautifully and mysteriously around the world of human imagination. In nearly all ancient cultures the snake was the symbol of healing and wholeness”. (1995, p. 140).

And, Esther Harding points out that in ancient mythology the snake represents creativity and renewal,

“In the first place the serpent was credited with the power of self-renewal because of his ability to change or renew his skin. The power was felt to be akin to the power of the moon which renewed itself month by month, after its apparent death”. (1971, p. 53)

From this, it appears that the tincture is closely related to the redemption and resurrection of the serpent – instinct infused with wisdom – which gives us the power to heal, create and renew the world and ourselves. And in doing so, the world becomes more real, more alive, and more amazing, and so do we.

The Ancient Bristlecone Pine, White Mountains, California

I am now over 11,000 feet high. The air is thin and a cold, and a dry wind sweeps across my face. The landscape is stark and rocky. Only the thinly scattered Bristlecone trees and flowering shrubs give evidence to life. The Bristlecone are an anomaly, considered the oldest living beings on the planet, reaching ages of over 4,500 years old. How interesting it is that the oldest trees are not the tallest. Nor are they green with abundant leaves. They are not showy and glamorous. They grow from the inside out, shrouding their new growth with dense, gnarled bark. They appear like old women, wrinkled by the burden of life, joyous in the magic of survival. If any words describe the Bristlecone it is aged, weathered, and wise. Without much thought, I walk to a particular tree and carefully cradle myself in its lap. I rest here for a long, long time. Golden droplets of sap rain on me.

Further Reading

Chevalier J. & Gheerbrant, A. (1996). The Penguin dictionary of symbols

(J. Buchanan-Brown, Trans.). London: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1969)

Edinger, E. (1985). Anatomy of the psyche. Chicago: Open Court.

Harding, E. (1971). Woman’s mysteries ancient and modern. New York: Harper Colophon Books.

Hogan, L. (1995). Dwellings: A spiritual history of the living world. New York: Touchstone.

Jung, C.G. (1967). The visions of Zosimos. In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 13). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published in 1954)

Jung, C. G. (1966). The aims of psychotherapy, In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 16). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published in 1931)

Jung, C. G. (1966). The psychology of transference. In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 16). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published in 1946)

Jung, C.G. (1968). Psychology and alchemy. In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 12). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1953)

Jung, C.G. (1969). The psychology of the kore. In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 9i). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1951)

Jung, C. G. (1969). Transformation symbolism in the mass. In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 11). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1954)

Jung, C. G. (1976). The visions seminars I & II. Zurich: Spring Publications.

Jung, C. G. (1977). Jung speaking. (W. McGuire. & R.F.C. Hull, Eds.), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kerenyi, C. (1967). Eleusis: Archetypal image of mother and daughter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Kerenyi, C. (1969). Kore. In R.F.C. Hull (Trans.). Essays on a science of mythology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Killion, T. & Snyder, G. (2002). The high Sierra of California. Berkeley: Heyday Books.

Luke, H. (1989). Dark wood to white rose: Journey and transformation in Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York: Parabola Books.

Luke, H. M. (1990). Woman, earth and spirit. New York: Crossroad.

Neumann, E. (1994). The fear of the feminine. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and memory. New York: Vintage Books.

Tanahashi, K. (Ed.). (1985). Moon in a dewdrop: Writings of the zen master dogen. New York: North Point Press.

Vaughan, T. (1561). The allegory of the mountain. The alchemy website. Retrieved July, 30th, 2003 from http://www.levity.com/alchemy/lumen2.html

Wilhelm, R. (1988). Keeping still. Parabola, XIII (4), 86-88

1 For a full reading of the myth see Homeric Hymn to Demeter in Meyer, M. (1987), The Ancient Mysteries: A Sourcebook, published by HarperCollins.

2 Actually, there are three feminine principles at work here: Persephone, Demeter and Hecate. As the myth illustrates, Hecate is the goddess of the moon, the mercurial goddess, who acts as a mediator between Demeter and Persphone.

Posted in Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

Preface: This is a slightly longer version of an essay I wrote the for the upcoming issue of Circles on the Mountain, a journal published by the Wilderness Guides Council. The essay is about storytelling and mirroring, a practice we teach at the School of Lost Borders, initially created in this form by Steven Foster and Meredith Little. If you are unfamilar with mirroring and are interested in learning more, here is a a useful article written by friends at Naropa University. I’ve been co-teaching mirroring trainings at Lost Borders for about ten years, so it is a practice that is especially near my heart.

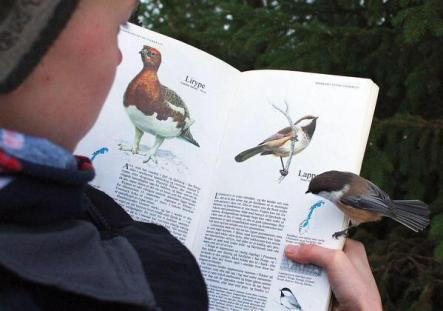

It’s a crisp September morning in the meadow above Baker Creek. All fifteen of us are huddled tightly in a circle; beach chairs and Crazy Creeks, the river nearby lined with gnarled cottonwoods and tangles of wild roses. This is the final day of the mirroring training, and we’re ending with a punch! The stories have spun us together, mesmerized us into a unified whole. Images fly about like birds. How could such strange and remarkable words come out of the mouths of these people?

It is no wonder that at Lost Borders we talk so much about mirroring. What is this practice? Really? And more so, what is it not? We know that mirroring is deep listening and reflection. And we stress that mirroring is never about fixing or resolving. No, we claim, the aim of mirroring is always to empower and validate the gifts already present in the story. But even still, mirroring mystifies me. It is such a simple practice and yet something occurs that I just can’t fully grasp. What is it that draws us down so deep? What loosens our tongues, allowing words to fly freely? What gives rise to such tears and ineffable joy? Indeed, part of what we experience remains hidden, like a coin in a magician’s hand.

In my Jungian studies, I discovered the following quote by Marie-Louise von Franz, which offers some insight into this hidden aspect of mirroring, which she calls the “mysterious point of contact.”

“The mysterious point of contact between the two systems appears to be the center of a sort of pivot where psyche and matter meet. When an individual enters into relation with the forces of the pivot, he finds himself close to the sphere of “miracles” which seemingly could not occur without a corresponding attitude on his own part.”

From the Alchemy Website

Although von Franz is presenting an obscure idea, I simply think of the “two systems” as two people – the storyteller and mirror – and the “pivot” as the story itself. Von Franz is actually referring to the phenomenon of synchronicity, those moments where the inner realm of the psyche and the outer world of matter merge in meaningful concurrences. But to me, this sounds a lot like storytelling and mirroring, which, as we have seen, tends to attract synchronicity. How many times has that hummingbird flown into story circle at the exact right time? Or the mirrored words touch on the beating heart of an unspoken truth? How many songs have we shared, unknowingly, between basecamp and those on their solos?

And what is the “corresponding attitude” that von Franz refers to? In mirroring, I believe, we would call it love.

When we “teach” mirroring one of the first things we mention is that above all else mirroring is an act of love. If the listener can fall in love with the story, and thus, the storyteller, than the “mysterious point of contact” will be met despite the actual words being spoken. And when this happens, it feels like magic.

Henry Corbin, the Sufi philosopher and mystic, speaks of love as the force of imagination, the entryway into the Mundus Imaginalis, the Imaginal World. For Corbin, the Mundus Imaginalis is a place similar to von Franz’s mysterious point of contact, a place that exists between our knowing and not knowing, but is palpably real. It is a place; he writes, that is

“both intermediary and intermediate … a world that is ontologically as real as the world of the senses and that of the intellect. This world requires its own faculty of perception, namely, imaginative power.”

When love pulls us through the threshold of the story, we enter into this realm of imagination where anything is possible. It is love that calls us out of our limited notions of reality and each other. This is not gushy, feel-good love, but love for life.

I confess I understand little of Corbin’s work. But I like his flavor. I like that he recognizes the Imaginal as something more than fantasy; that the Imaginal is a real realm that exists beyond our brains. Yes, the Imaginal depends on our ability to perceive, but the images that appear have a life of their own. It is like the animals that come to us in our dreams. They need the dreamer in whom to appear, but they don’t belong to the dreamer. These visitors just happened to pass through in the night.

And so it is with the stories that we hear in our councils. Consider all the images that arrive in our telling! How in mirroring we empower not only the storyteller but also all the beings that have fed the story. The stones, junipers, scrub jays, and foxes. In a time when the world feels so small, the Imaginal opens us up and makes it big again.

One of the most profound books I have ever read is James Hillman’s, The Thought of the Heart & the Soul of the World. It is a book attributed to Henry Corbin. Hillman begins with these words,

“You who have been privileged at some time during his long life to have attended a lecture by Henry Corbin have been present at a manifestation of the thought of the heart. You have been witness to its creative imagination, its theophanic power of bringing the divine face into visibility.”

“Thought of the Heart”; “creative imagination,” bringing the divine face into visibility.” These are the clues to the underlying workings of storytelling and mirroring.

The thought of the heart, unlike the rational head, is not locked in certainty but is free like a river to meander over stone, to pool up in an eddy and then let go. And it is of the heart because it is love that keeps the river flowing, refusing to dam that which it loves. Anytime we fall under the spell of fundamentalism or the need for certitude, we have forsaken love. As Hillman writes, “When we fall in love, we begin to imagine; and when we begin to imagine, we fall in love”.

Creative imagination breaks the chains of our literalism, and it’s incessant need to make all things purposeful. When someone asks, “Does mirroring work?” “Is it beneficial?” I get stymied. I don’t know how to answer. “Yes,” “No,” “I don’t know.” Such questions are impossible to answer because they inadvertently trap us in the mechanism of cause and effect thinking, the very thing we wish to avoid in mirroring. When our stories are taken literally, mirroring turns into a technique, and all the living images become nothing more than psychological debris.

I am not saying that mirroring doesn’t have psychological merit. We all know that it does. But psychological profit is not the reason for mirroring. This is why, I believe, it is a great disservice to market vision fasting and wilderness rites of passage as a self-help endeavor. It’s not. Let’s get this clear. Vision fasting will not lead to a happier life, better sex, or whatever. For as long as humans have been fasting in the wilderness this has never been the case. Think of St Jerome out in the desert, hungry and alone, pleading to God to strip him bare! But vision fasting will allow us a glimpse into a world that is not confined to our wishes. A world much bigger than ourselves. A living and infinite world. And what could be better than that? And in falling in love with this world, we, of course, feel a deep desire to give back to it. To preserve it, and make it better. This is why incorporation – giving back to one’s community – is so crucial. Incorporation is the continuation of love.

But what does Hillman mean by bringing the divine face into visibility? Although it might sound esoteric, Corbin maintained that everything has its angel. Not an angel in the literal sense as an ethereal being with wings, but a presence that reflects each thing’s true essence. Tom Cheetham, a Corbin scholar, writes, “The Angel is the immediate source of the personal face of every being. For anything whatever to be present, it has to be present to someone, and it has to be regarded, looked at, in a mutual, personal relation”. Today, we might call this angelic presence “soul.”

During the mirroring training, we always remark how easy it is to fall in love with the storyteller, even when we don’t particularly like that person! I believe this is because we fall in love with that person’s angel, or soul. In this life, we all wear the dirty clothes of our human fallibility and interpersonal muck. But the angel shines through the dirt, or because of it, revealing the face or our shared humanity. We fall in love with the angel that is reflected in our own. Storytelling and mirroring are therefore an endless call and response between our very human selves and the soul of each person and living being, between the Soul of the World and us.

Ultimately, Corbin shows us — and I think this is the greatest gift of storytelling and mirroring — that when our hearts are open and rid of our fixed ideas, we see the world not as a dead thing, but as a place made of breathing, feeling, individual sentient beings. In these difficult days in which the imagination has become hobbled by apocalyptic literalism and malignant politics, this call to the Imaginal is of utmost importance.

Call and response. Call and response.

Let us not ever, ever let the story come to an end.

Works Cited

Cheetham, T. (2015). Imaginal love: The meanings of imagination in Henry Corbin and James Hillman (Kindle Version). Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/

Corbin, H. (1972). Mundus imaginalis, or the imaginary and the imaginal. Spring, 1-19

Hillman, J. (1981). The thought of the heart & the soul of the world. Spring Publications, Woodstock, CN.

Posted in Uncategorized | 5 Comments »

What can we gain by sailing to the moon if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves? – Thomas Merton

Richard Wilhelm, Chinese scholar and theologian, told the story of the Rainmaker to Carl Jung while at a gathering of the Psychological Club in Zurich in the 1920s. It is a story that so impressed Jung that throughout the rest of his life he repeated it as often as he could, sometimes annoying his audience with the endless retelling. But good stories should be retold, over and over, penetrating our dim consciousness a little deeper each time. Wilhelm referred to the story as true, and although truth comes in many forms, I believe that Wilhelm’s claim is not a plea for legitimacy, but rather a call for deliberate attention.

And so the story goes:

In the ancient Chinese province of Kiaochou there was a drought so severe that many people and animals were dying. All the religious leaders attempted to solicit relief from their gods: the Catholics made processions, the Protestants said their prayers, and the Chinese fired guns to frighten away the demons of the drought. Finally, out of desperation, the town’s people called upon the Rainmaker, and from a province far away there appeared a shriveled up, old man. The old man immediately requested a small hut on the outskirts of town, where he locked himself up for three days and nights in solitude, and then, on the fourth day, it rained. In fact, it snowed at a time when snow was not expected.

Wilhelm, who was allowed to interview the Rainmaker, asked him how he made the rain, and the old man responded by exclaiming that he did not make the rain, that he was not responsible! Not satisfied with this response, Wilhelm pressed on, “Then what did you do for these three days?” And the old man explained that he had come from another province where things were in order with nature, but here, in Kiaochou, things were out of order, and so he himself was also out of order. Thus, it took three days to regain Tao and then naturally, the rain came. (Adapted from C.G. Jung, CW 14, pp. 419-420, note 211).

Upon hearing the story of the Rainmaker, like Wilhelm, I cannot resist asking what happened inside that hut for those three days, and how was the rain made? Is the Rainmaker harboring a great secret? Is he being truthful? Does he not feel the least bit responsible for making the rain? Or is this story just a quaint parable, illustrating a spiritual lesson that has no bearing on actual physical events, such as rain? In other words, is Tao only an inner, personal phenomenon, or has it any bearing on the physical world? With the severe drought conditions in California, and global warming increasing each day, these seem like important questions to answer.

And yet, the point of the Rainmaker story is precisely this: That the inner realm does touch upon the outer; that the Rainmaker’s ability to achieve Tao (whatever that means) did touch upon the clouds, the moisture, temperature, and wind, which allowed it to rain and even snow. It is a mystifying idea, indeed, because we in the modern Western world are not trained to see this interdependence. But, in a place far beyond vast oceans and time, as we see in the Rainmaker story, all things are interconnected, including that which we think of as inner and outer. As much as the ego insists on its separate singularity, ultimately, we are not our egos, imprisoned inside our skin, or inside our skulls, however you will have it. When I ask my students where the unconscious resides, most of them point to their bellies, as I do. When I ask about the ego, immediately fingers go to the head. Never does one point to a glass of water, to a tree, or to the surrounding air, even though without these things none of us would exist.

And still, I wonder, what did he do in that little hut for three days? How did he make it rain?

As far as my pea brain can fathom, to be in Tao, is to recognize our oneness with all of nature, or more so, to recognize that we are nature, that humans and nature are the same. The philosopher Alan Watts says it is a fundamental scientific truth that human organisms (or any organisms) cannot be studied or known apart from the environments in which they exist, and for this reason, ecologists speak not of organisms in environments, but of organisms—environments, indicating the inseparability between the two. We are not born into nature, Watts continues, but from it. This subtle, but significant shift in language transforms us from being aliens who invaded this planet, to full-fledged child-members born from it. And yet, although the scientist knows this, rarely does he feel it (Watts, Does it Matter, p. 90).

On the other hand, “A mystic is one who is sensibly or even sensually aware of his inseparability as an individual from the total existing universe” (Watts). The mystic and scientist both understand our inseparability from nature, yet perhaps the mystic is different because he feels it and lives it as so. The Rainmaker, obviously, felt the truth of this oneness, although it took him three days to get there. I like the idea of being a mystic-scientist, but for me, it might take three hundred years. I am still learning to identify the flowers in my backyard, or how to grow a sweet tomato.

But, on this afternoon, as I sit on the knoll over looking the canyon in Death Valley, I ponder the story of the Rainmaker and the meaning of Tao. Each year, I go into the desert for four days and nights of fasting and solitude with my friends from Lost Borders, and this is third day of uncomfortably hot weather, although it is only February. In spite of the heat, I muster up a playful spirit and pretend that I am a creosote bush inseparable from the rocky wash in which it grows, awakened by the afternoon breeze, waiting upon precious rain. I am no different than the creosote, or the rocks, or the tiny cactus that pricks my butt. And more so, even when I fail to recognize I am no different (which is most of the time), I am still no different. Which reminds me of the Zen teaching that says we are all Buddha, each and every one of us, no matter how screwed up we may feel. Even when I fail to feel my inseparability from nature, it is impossible to be separate. Perhaps, this is what the drought has to show us even if in the most painful of ways: that, no matter how separate from nature we imagine ourselves to be, we still rely on rain.